The Louvre stands as one of the best art museums in the world. It is also one of the largest. You will find navigating its vast halls daunting without a plan. The museum overwhelms even seasoned visitors. Because there are 35,000 objects on display, guidance on things to see at the Louvre will greatly enhance your visit.

You cannot see everything in a single visit. However, you can focus on a concise list of masterpieces. This list highlights the Louvre museum’s top attractions and must-see works. Prioritize these if you are a first-timer.

Here is an essential list of the top 13 things to see at the Louvre. If you want a top 10 things to see at the Louvre, most of these masterpieces qualify as essentials.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace

This marble statue is not just another old sculpture. It is one of the oldest and most influential statues in existence. You have probably seen many Greek-style statues in other museums. Most are Roman copies. The original Greek statues, like the Winged Victory of Samothrace, are much older and far rarer.

We do not know the name of the sculptor. Yet, the technical mastery and the dynamic depiction of wind in the drapery set this work apart. It has influenced Western sculpture for centuries. The Winged Victory of Samothrace is a must-see for sculpture lovers.

- It is one of the very few surviving original Greek statues.

- The sense of motion and energy is unique among ancient sculptures.

- You will find it much larger in person than in any photo.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace impresses with its size and presence.

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

Next, you should seek out Antonio Canova’s Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss. This statue captures the tender moment when Cupid revives Psyche with a kiss. Canova sculpted both figures from cold marble. Yet, the work pulses with romance and intense emotion. The statue highlights the enduring power of love and art.

Antonio Canova mastered marble carving.

The Venus de Milo

The Venus de Milo is one of the most famous statues in the world. She stands as a symbol of classical female beauty. Her missing arms do not detract from her impact. The French promoted the statue heavily after acquiring it from Melos in 1821. They even tried to claim it was older than it is.

Despite this, the Venus de Milo continues to inspire awe. Many visitors rank her among the top 10 things to see at the Louvre. She remains a highlight for art lovers.

The Venus de Milo continues to captivate millions.

The Raft of the Medusa

The story behind this painting is gruesome. The French frigate Medusa wrecked off Mauritius. Only 15 out of 151 sailors survived after days of horror at sea. Theodore Gericault’s painting captures the drama and despair of the moment. The painting marked a shift from Neo-classicism to Romanticism.

You will find it shocking and unforgettable. It stands out among the most dramatic paintings in the Louvre.

The Raft of the Medusa is a masterpiece of emotion and drama.

Liberty Leading the People

You will likely recognize this painting. It depicts Liberty as a bare-breasted woman leading fighters during the July Revolution of 1830. Eugène Delacroix painted it to symbolize the French Republic and revolution.

- The painting does not hide the violence and suffering of the revolution.

- It became an icon of French liberty.

- At 8 by 10 feet, its scale matches its drama.

Liberty Leading the People is a powerful symbol of freedom.

The Coronation of Napoleon

Jacques-Louis David painted this monumental work. The painting measures 33 by 20 feet. Napoleon commissioned it to immortalize his coronation in 1804. The painting includes many famous figures from French history. You will notice the painter included himself in the scene.

The Coronation of Napoleon impresses with its scale and detail.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus

This statue offers a surprise. At first glance, you see a reclining woman. However, the figure is Hermaphroditus, depicted with both male and female features. The cushion beneath is a separate addition by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

You will marvel at:

- The lifelike softness of Bernini’s marble cushion.

- The bold subject matter for ancient and modern audiences.

- The blending of Greek and Roman traditions.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus challenges expectations and showcases artistic skill.

Hammurabi’s Code

You may remember Hammurabi’s Code from school. This ancient stele dates to 1754 B.C. It contains some of the world’s oldest written laws. The phrase “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” appears here. The text reveals much about life in ancient Babylon.

I.M. Pei’s Pyramid

In 1984, I.M. Pei designed a new entrance for the museum. He created a steel and glass pyramid. Parisians debated its modern look for years. Today, the pyramid stands as a symbol of the Louvre. Visitors flock here for photos.

- The pyramid blends modern design with historic surroundings.

- It provides an iconic backdrop for your visit.

- You can use it as a central meeting point.

I.M. Pei’s pyramid is now one of the most recognized features of the Louvre.

The Lamassu

You will find these ancient statues stunning. The Lamassu are winged bulls with human heads from ancient Assyria. They guarded palace entrances as early as 3000 B.C. Their craftsmanship and design are extraordinary.

These statues:

- Pre-date most other works in the museum.

- Blend human and animal features in a unique way.

- Remind visitors of the long history of art and civilization.

The Lamassu captivate with their age and artistry.

The Dying Slave and the Rebellious Slave

Michelangelo sculpted these two statues for Pope Julius II’s tomb. However, the tomb project never reached its original scale. The statues show Michelangelo’s ability to capture deep emotion in marble. They remain among the most moving Renaissance sculptures in the Louvre.

Michelangelo’s Slaves convey emotion and artistic mastery.

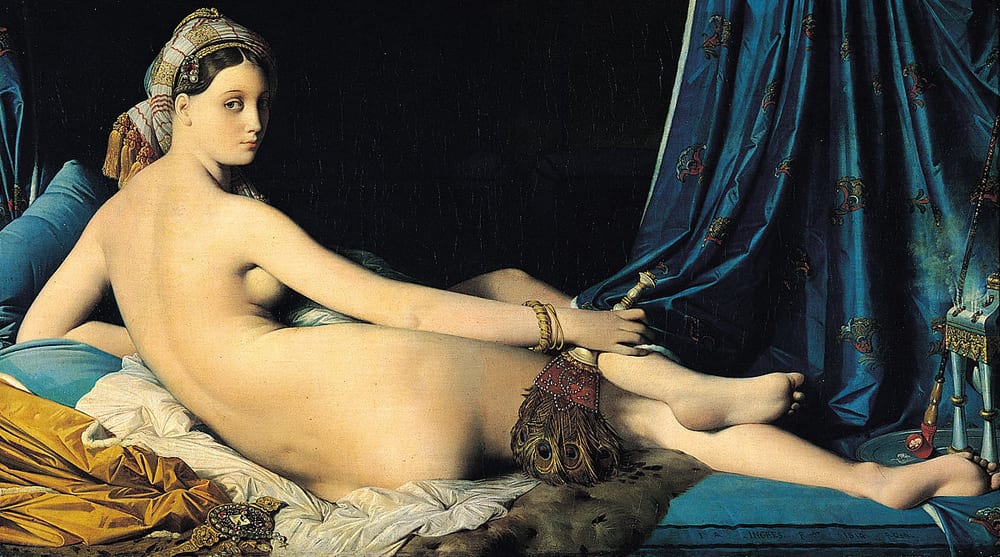

Grande Odalisque by Ingres

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted Grande Odalisque in 1814. The work shows a nude woman in a harem. Ingres exaggerated her anatomy to heighten sensuality. The painting sparked controversy for its eroticism and its portrayal of Eastern women.

Grande Odalisque stands as a striking and provocative painting.

The Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa using a technique called “sfumato.” The result is a lifelike, three-dimensional effect. Her enigmatic smile fascinates millions. The painting became famous after its theft in 1911 and subsequent recovery. Today, the Mona Lisa attracts the largest crowds in the Louvre. Plan to see it during off-peak hours.

Take a Guided Tour

If you’re planning to visit the Louvre and want to experience more than just the highlights, the Complete Louvre Tour: Mona Lisa & Beyond is the perfect way to dive deeper into the museum’s vast collections. Led by expert art historians, this intimate 3-hour tour takes you beyond the famous Mona Lisa to discover hidden gems and masterpieces like the Venus de Milo and The Wedding Feast at Cana. With a small group size and skip-the-line access, you’ll get an up-close look at iconic works without the crowds. Whether you’re a seasoned art lover or a curious first-time visitor, this tour offers an insightful and stress-free way to explore the Louvre’s world-renowned treasures. Let the experts guide you through the stories behind each piece, making your Louvre visit truly unforgettable!

FAQ: Things to See at the Louvre

What are the must see at the Louvre for first-time visitors?

The must see at the Louvre for first-timers include the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, Winged Victory of Samothrace, Liberty Leading the People, and The Raft of the Medusa. These are some of the Louvre museum top attractions and are considered famous things in the Louvre that everyone should experience.

Are there any tips for avoiding crowds at the Louvre museum top attractions?

To avoid crowds at the most famous things in the Louvre like the Mona Lisa or the Venus de Milo, visit early in the morning, late in the afternoon, or during evening hours when available. Booking a tour that offers skip-the-line access can also help you maximize your time.

How long should I plan for my visit if I want to see all the must see at the Louvre?

To see the top attractions and the things to see at the Louvre museum, plan for at least 3-4 hours. If you want to explore more deeply or see specific collections in detail, a full day may be needed, but most visitors focus on the top 10 things to see at the Louvre during a single visit.

What are some unique or lesser-known things to see at the Louvre?

Beyond the top attractions, don’t miss Hammurabi’s Code, Sleeping Hermaphroditus, the Lamassu, and the Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave by Michelangelo. These are fascinating and historic works that add depth to your Louvre experience.

Don’t miss our signature, small-group walking tours at some of the most exciting attractions in Paris.

Check out the Complete Louvre Tour, and learn all about history and art!